- Internet: Medium For Communication, Medium For Narrative Control

- Part 5 — Adapting

- Section 2 — Legality, Transparency, Accountability, The Nations Intervene

Table Of Content

- Introduction

- Part 1: The Artifacts And Spaces

In this part we'll describe the important artifacts and places. Going

over these essential, but basic, pieces is mandatory to understand how

they come into play as tools.

- Part 2: The Actors and Incentives

In this part we'll go over how the previous elements are put into work

by the different actors, who these actors are, what are their incentives,

and the new dynamics.

- Part 3: Biases & Self

In this part we'll try to understand why we are prone to manipulation,

why they work so effectively or not on us, and who is subject to them.

- Part 4: The Big Picture

In this part we'll put forward the reasons why we should care about

what is happening in the online sphere. Why it's important to pay

attention to it and the effects it could have at the scale of societies,

and individuals. This part will attempt to give the bigger picture of

the situation.

- Part 5: Adapting

In this concluding part we'll go over the multiple solutions that have

been proposed or tried to counter the negative aspects of the internet.

- Conclusion & Bibliography

- Laws and Governments as Moral Arbiters

- Free Market Competition Is Not Enough, Privacy as a Human Right

- Balance Between Sociality And Privacy

- Consent, Ownership

- Consent, Persuasive Tech

- Consent, Right Of Non-Reception

- Accountability, Securing Data

- Accountability, Content + Gatekeeping

- Transparency, Processing, Usage, Analytics, and Partnerships

- Transparency, Disclosing Sponsors

- Transparency, Bots

- Example Laws

- Drawback Of GDPR

- Standardization Of Data

- Privacy as a Utility, Government Monopoly on Identity

- Social Media as a Utility

- Digital Identity, Identity as a Public Infrastructure

- Examples of Implementations

The market and corporate self-regulation have their limits. They cannot

in themselves be sources of morals and ethics. This is the realm of laws,

the legislations that governments make are the real arbiters of duties

and rights.

The governments, as state entities, can impose the rules that should be

followed to be able to act on their territories. However, laws are bound

by geographical areas and as such cannot be international. They can only

be inter-governmental if treaties and partnerships are in place. Companies

can decide to comply to different regulations in different areas to be

able to operate on these markets.

The best defensive tactic for nations is always legislations, instead

of leaving it as a free-for-all medley. This is what we’ll dive into:

when governments intervene on the internet.

The neoliberal mindset abhors this return to authorities because of the

general lack of truth we’ve seen earlier. Yet, who do we trust more

and want to grant more authority to: private for-profit entities on

not-so-free markets or our governments and their legal systems?

In this section we’ll focus on rights and not regulations related to the

private sector. Things related to transparency, accountability, consent,

ownership, utility, and identity.

We’ve already seen market regulations for fair competition, conflicts of

interests, collusions, antitrust, and others that are currently discussed

or getting in place around the world.

Despite these new market regulations, many of the internet giants and

their partners still stand tall and confident that their business model

isn’t going to fall. Either because of nifty bypassing techniques, or

because of lobbying. That’s why such regulations don’t coincide with

what most of the netizens actually want.

For example, many recognize and want privacy to be a basic human right,

part of human dignity. The “right to be let alone”.

Similarly, we’ve previously seen how researchers and human right

activists are now thinking, when it comes to brain data privacy, of new

rights such as: cognitive liberty, mental privacy, mental integrity,

and psychological continuity.

On the surface, these will only be fancy words of wisdom and

considerations if they aren’t written in laws, legally binding. Otherwise,

companies could lie. Governments have to ensure the spirit of the laws

are applied and not mere market regulations. It would be catastrophic

if no such basic rights are in place and sensitive personal information

such as brain data become common place on the internet.

The question today are related to who’s in charge of the privacy and what

kind of balance we can have. Can our information be both a currency for

some and protected as a right for others?

The actual implementation is a hard problem when it comes to privacy

guidelines as there is a balance between sociality and privacy: sociality

has always required the voluntary abandonment of privacy. In order to be

social we must give up some of our private time and space to share it

with others.

This takes new forms online where sociality is taken at the expense

of privacy and social autonomy. Today, it rests mostly upon digital

records and archives in the hands of private companies that track our

social behavior. As we’ll see, it could be more attractive to have these

records switch hands from the corporate world to the public sector.

The legal world is a tricky one, the laws need to be written so that

they cannot be abused, covering as many aspects of an issue as possible

to not leave room for ambiguity.

The first clarification that needs to be made is about defining what

is meant by personal data and who is the actual owner of such data. We

already gave our definition in the data and personal data section in

part 1 of this series.

Personal data is any information that can be used to directly or

indirectly identify a person, an attribute currently attached to them,

a behavior, a preference or interest, personal history, anything.

These include things such as name, phone number, address, email,

schoolbook, credit scores, geolocation, travel logs, interests,

information about past purchases, health records, insurance records,

online behavior, etc..

We call the person to which the personal data belongs a data subject.

Having this definition in a text law is the starting point.

Then, comes the issue of ownership of the data. As you might remember,

we called the person which data was extracted from the data subjects.

Hence, we need to specify what are the rights of ownership they have

over their data, and in which cases they need to give consent to allow

others to access it.

The consent itself needs to be delineated properly. We need to know what

can be done with the data, for what purpose, for how long the retention

can be, and most importantly, if consent is transferable. One company

getting approval to access data could share this data with other entities,

the transitive consent and transitive propagation of data.

Ownership also rhymes with control. Laws might want to spell out if

a data subject should or should not be able to perform corrections,

updates, or erasures of the data they have generated.

Yet, consent makes no sense if people can be coerced into giving it, if it

isn’t informed consent. This is the case online with the use of persuasive

technology, both to extract data and be subject to advertisements. They go

hand in hand. Thus, the legal domain has to take this into consideration

and posit whether such technology is allowed or not.

Additionally, it could make the parallel with gambling, alcohol,

cigarettes, or other questionable products, basically limiting

advertisements on mainstream channels.

Furthermore, when it comes to consent, the law has to deliberate if

persuasive algorithms and designs should be allowed on children or not

— age is often a factor when it comes to consent. Persuasive design

and dark patterns could be made illegal altogether.

When it comes to advertisements, it has to be decided if consent needs to

be given even before receiving them, or whether the person can at a later

time refuse to receive them, retracting it.

The right of non-reception, is the right of someone not wanting to be the

recipient of ads. If such right is in place, companies could be pursued

in court and fined if they advertise to people who have opted-out of them,

or to those who haven’t opted-in depending on how the law is phrased.

Such right is generally associated with online cookies, the right to

not be traced online.

Offline, it is associated with not receiving ads in mailboxes, or at

city-scale, to not have or limit billboards. This is also a method to

avoid material waste.

Still, these can easily be bypassed with an ingenuous use of product

placement and sponsoring instead of direct ads. Or even turning customers

into brand evangelists, which is the norm with neoliberalism as we’ve

seen earlier.

Once the personal data is stored, it could and is expected to be subject

to access restriction and accountability. The companies and entities

we have trusted with our data should be responsible for their safety so

that nobody else retrieves them.

Thus, governments could create bodies and processes to verify the

security, integrity, and confidentiality of the data storage in companies

and entities that choose to host it. With the increase in quantity

and types of consumer data, it is imperative to have such measures in

place. We’ve heard too many data leaks stories in the news lately,

either from hacking or rogue employees.

Arguably, even standards like the PCI-DSS, if applied to personal data,

might not be enough without real-time checks.

Along with the responsibility of storing the data, laws could dive into

the accountability related to the content of the data itself. Should

platforms be accountable for the content it hosts, or should it be the

data subjects themselves, or both?

This would in turn create new gatekeepers: a monitoring and reviewing of

the content published and hosted. This could also include the algorithms

that are used to promote content.

These algorithms have acted as amplifiers of extremism, enlarging

dangerous fringe communities, and pushing biases (racial or

others). Currently, the entities that are using them have been hiding

behind the fact that these are algorithms, and thus “mathwashed”

removing their responsibility because “they have no conscience of their

own”. The myth of the impartial machine.

Many of the social network platforms, in the USA, have been avoiding

monitoring the content posted on them by referring to the USA first

amendment of free speech and the 1996 USA Communications Decency Act,

shielding them from liability for content posted by their users.

However, this only applies to the USA and the different branches of the

same platforms are able to monitor content in other countries.

To thwart this, governments need to either consider social media as news

platforms, or find methods to strengthen the institutions that create and

distribute reliable information: mainstream media, academia, nonpartisan

government agencies, etc..

Once social media are part of the mainstream news system, the gatekeepers

are back in place, they’ll have to uphold journalism standards for the

content posted on them.

Governments can also enforce social networks to pay news that get

published and distributed there, indirectly re-strengthening the local

media publishers.

Apart from news, the platforms can be held liable for the undesirable

content that is shared there.

This is most important when this content is shared in a public space

that children can access. Laws can ensure children won’t be subject

to neither surveillance, tracking, and be protected from predatory and

dangerous content.

Contrary to popular belief, in the USA the COPPA (Children’s Online

Privacy Protection Act) only takes the advertisement and tracking of

children, but not whether the platforms are responsible for the content

to which they are subject to. The Child Online Protection Act of 1998

(COPA, yes similar name) is the one that has the intent of preventing

minors from accessing obscene material on commercial websites in the USA.

Most countries already protect their children against being subject to

harmful material on public commercial channels.

India’s new intermediary liability and digital media regulations takes

a step further and forces content to be traceable to its source, to be

able to verify social media users, and rapidly take down non-consensual

sexually explicit content and morphed/impersonated content within 24h

of being notified.

With the same mindset, some countries have laws specifically to take

down online hate speech and incitations of violence or terrorism.

If we can’t blame the hosts of the content, we might want to hold

the people that generated it accountable. This, in turn, should make

black propaganda ineffective. However, because most online-interactions are

anonymous, it is very hard to do.

A solution to this would be to attach a real identity to whoever uses,

posts, and creates online content, this is what the concept of digital

identity is about.

Online platforms that allow bots could also be forced to tag them as such,

making it clear to everyone that these aren’t real humans.

We’ll discuss this later, but as you can expect, while it does bring

back gatekeepers, it also could create more social cooling.

Agreeing that the personal data should only be used for specific purposes

is fine, but there needs to be some guarantee behind the agreement. For

trust to set in, transparency is mandatory.

One type of transparency is about understanding why and how the

recommendation engines, the curation systems of the internet, work. From

advertisements, to news feeds and other algorithms. Having a clear

picture of their inner-workings would help us make better decisions and

responsibilities instead of overly relying and trusting them.

With the recommendation engines come the analytics, the categorizing,

ranking, rating, and scoring of data: how data is processed

internally. Transparency is about knowing where and how our data will

be used, in what process.

It could be hard for companies to accept transparency at this level

because that would mean opening their valuable extracted data storage

to the world.

The transitive propagation of data needs also to be transparent if it

happens. That includes disclosing who are the third parties that will

access the data, for which reasons, what data points they used, the

target audience, and who paid for the ads campaigns.

This type of financial accountability, full transparency regarding the

amount spent by companies on ads, also applies to political campaigns

sponsorship. Ad political campaigns, which on the internet were often

overlooked, would now have their layer of anonymity removed. Yet again

removing black propaganda and state-linked accounts from the equation

and making microtargeting less obvious.

Many legislatures, regions, states, governments, authorities, and

countries have erected or proposed laws to tackle the things we’ve seen,

let’s mention some of them.

Related to the financial accountability, the Honest Ads Act, is a bill

in the USA that was proposed such that online services would be required

to reveal the description of the target audience of ads campaigns.

However, this bill wasn’t passed yet in favor of self-regulation. The

USA, in general, is a laggard on the domain of privacy as it feels more

threatened by the intervention of the state than the market.

Still, in 2018, the California Consumer Privacy Protection, a legislature

passed in California (a USA state) would guarantee users in that region

the right to know what data is being collected, and opting out of the

sale of their data.

This opt-out approach isn’t the best but it’s a start.

Others might find that there needs to be a stronger data protection,

that it’s part of human dignity and that it shouldn’t be threatened by

any kind of intrusions. In that view, privacy and ownership over our

private data is a default and not an opt-out.

The European Union was the first in 2016 to spear-head this change by

rolling out the largest attempt at protecting user data with the General

Data Protection Regulation.

Privacy laws are not new, for example France’s data protection law dates

back to 1978, and the EU already had Data Protection Directive law

about the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms in the processing

of personal data, dating from 1995. However, the GDPR is an extension of

all this with modernization, clarification, and making it actionable. It

is a move that has spurred other states to enforce similar laws. It also

gives them more confidence in intervening against the internet behemoths,

which they wouldn’t dare attack before.

The French data protection law ensures the following rights:

Personal data must be collected and processed fairly and lawfully for

specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes, and with the consent of

the data subject. In addition to the right to consent, data subjects have

been given the following rights: right to be informed, right to object,

right of access, right to correct and delete information, and right to

be forgotten.

These have been mapped unto GDPR to hold data processors accountable

when manipulating data that isn’t mandatory for the functioning of the

service. It defines clearly what is meant by personal data, what it means

to process it, and what is required of organizations and entities that

process it.

The organizations are expected to have a management procedure in place

to keep the data safe and secure from breach. That means specific

roles need to be in place, such as a Data Protection Officer, and the

risk management assured. They are held accountable for the privacy and

protection of the data, and data protection assessment can be performed to

ensure this is properly applied.

The data subjects keep their rights over their data. They should be

informed about the processing activities taking place, the data not being

used for any non-legitimate purpose. Their explicit consent needs to be

requested for its usage and collection. That means the data subjects

have the right to update/correct and erase their data. Additionally,

the data subject can ask to see which data is held about them and control

whether its transfer can happen between third parties or not.

Most importantly, regulators can ask for demonstrations of accountability

and impose fines for the entities that aren’t complying. This is the

clause that makes the difference with any previous laws.

After it was passed, the internet has been shaken. Most websites have

chosen to display annoying pop-ups/notification banners asking if users

want to allow their information to be shared with third parties. It

defaults to no but it is sometimes hard to manipulate and very intrusive.

Moreover, some companies are also allowing their users residing in

the EU to download the personal data that has been gathered, and give

them the possibility to delist it, essentially erasing it.

The way the GDPR has been applied by companies has given rise to more dark

patterns, persuasive technologies trying to trick users into accepting

to give their personal info.

Research has shown that only around 11.8% of consent forms in 2019 met

the minimal requirements based on the European law.

Multiple countries have their own privacy laws and acts, and many today

are modernizing and reforming them to add actionability like GDPR.

Some even include the right to data portability and the right to object

to marketing, the right of non-reception which we mentioned earlier.

Let’s take some examples.

Canada has the Privacy Act from 1983, which it is modernizing to be

similar to the GDPR in the Personal Information Protection and Electronic

Data Act. China’s Personal Information Security Specification that

took effect in 2018, and ratified in 2020 in the Personal Information

Protection Law, has more strenuous and far-reaching requirements than GDPR

applying to any personal data and not only sensitive personal data. The

UK has its UK Data Protection Act from 1998, which has been updated in

2018 to follow and supplement the GDPR, and is being updated today to

follow its own standards. The Irish Data Protection Commissioner (DPC)

upholds the same fundamental privacy standards as the EU. Similarly,

Australia has updated its 1988 Privacy Act and Australian Privacy

Principles to be like the GDPR. Russia Federal Law on Personal Data of

2006 regulates data processors to protect the defined sensitive personal

data against unlawful and accidental access. India’s PDP Bill of 2019

goes in the same direction as GDPR but is more integrated with Aadhaar

portability which we’ll see in a bit. Argentina is going the same way,

currently amending their laws to be like the GDPR. etc..

It’s apparent that most of the world is moving in the direction of

edifying laws to protect the privacy of the citizen from the private

corporate data brokers. Market regulations aren’t seen as enough.

Some nations take it a step further, considering the protection, privacy,

standardization, digitalization, and usage of identity to be the role

of the state and not corporations. The state should have a monopoly on

identity, just like it should, in theory, have a monopoly on violence

because it has the same destructive power.

As we said, sociality requires giving up a bit of privacy, and

the digitalization of identity is a requirement for the information

society. Some people are uncomfortable with the idea of making it the

job of the state and would rather have centralized private entities do

that. Yet we know that corporate incentives are only for-profit and not

the shared good, which could hinder the transformation of the society

into this new era.

Thus, some governments force the private sector to strictly follow

their privacy rules, while the public sector uses identity as a utility,

a part of public infrastructure for the public services.

This requires standardization, definition, transparency, and data

portability of digital identity. We’ll come back to this in a bit but

first let’s imagine social media as one of these services.

We already discussed social media as utilities in the social media

section of part 1. We said back then that for it to be a utility,

it should change from a want to a need, an essential infrastructure,

a necessity like electricity.

Social media could be said to be an integral part of information society,

in order to adequately take part in the 21st century as an individual,

and thus would be important to have the government provide it to remove

any profit incentives from it.

Some believe that current popular social media already act, feel, and

are considered by people like utilities. So they push forward the idea

of making them as such, just like the telecom sector or electricity

sector: a public service that is regulated by the government.

It would make it easier to ensure the protection of the

constitutional rights of users, such as freedom of speech in some

countries. Additionally, the government could enforce search neutrality,

modeled after net neutrality regulations — essentially assure equal

access for everyone.

Yet, others argue that making social media similar to telecom regulations

would be bad for the market, reduce innovation and growth because of

the lack of competition. This is a market view of the subject.

Moreover, it can be said that social media haven’t gained the status

of utility because countries don’t go haywire when they go down, that

there is always an alternative, they are still new and replaced every

couple of years.

Furthermore, from the neoliberal perspective, one that dreads authorities

and prefers seeing things as a free flowing market, not catching nuances,

this is the equivalent of the chilling rise of “authoritarianism”

and “fascism”. Words that are used as emphasis to display the attack

they feel towards their world view.

Still, there might indeed be a new kind of social cooling taking place

when we become owners of our social media, instead of having them

as private companies. State actors were already requesting personal

data from these companies and using them for their gain, as we’ve seen

before. Making them public utilities would instead force the general

public to keep it in check, as it would be something they would be

indirectly paying to keep running.

Another trend is the one of the digitalization of identity by

governments. This is the standardization of identification and identity

systems and management that become part of the public infrastructure.

In practice, this is more of a re-definition of national identity cards by

making them digital, interoperable, and accessible by all citizens. Having

it as an infrastructure means that all kinds of public and private

services can rely on it to verify reliably the identity of people.

This comes with a lot of challenges for governments as they have to

set in place the legal framework around the infrastructure, its usage,

regulations, auditability, traceability, transparency, and obviously

actually create a technology that is secure, confidential, keeps the

integrity, is scalable, and respectful of all individuals.

The capability of the identity system needs to be well-defined, from

authentication, authorization, roles, and delegations available. Some

government bodies and international standards have been created for

these identity management systems such as ISO, the EU eIDAS, European

Self-Sovereign Identity Framework, European Blockchain Services

Infrastructure (EBSI), and the GSMA Identity programme and Mobile Connect.

Like with social media as a utility, this comes with the same perception

from those who’d rather be surveilled by private companies than their

government. But with enough transparency and preparation, the most

digitally-skeptic can get on board, especially if the solutions are free

and open source as we’ll see in the next section.

So far, the implementations of digital identities by governments have only

been applied when it comes to accessing public services and KYC processes

when signing up for services such as telcos, energy, and banks.

Estonia, India, and China are countries that are leading the way. The

upside is convenience and an economic boost. According to McKinsey Global

Institute, countries that implement a digital ID scheme can boost their

gross domestic product by 3 to 13 percent by 2030.

Estonia has been rolling its digital identity program for the past

20 years. Technically, it is a mandatory 11-digit unique identifier

assigned to all citizens above the age of 15 that is stored along with

a public-private key pair in a PKI (Public-Key Infrastructure).

The default format of this digital ID is a physical card, an i-card,

similar to a credit card, passports, and sim cards: an embedded chip

(UICC) protected by PIN codes. Internally these circuit cards use secure

elements (SE) as a root of trust to store the sensitive information. We

generally refer to this type of technology as hardware security modules

(HSM). Other formats exist such as a mobile application that inspired

China’s version of it, I am not currently aware if the Chinese solution

additionally requires an UICC to be inserted in the phones.

The data is stored in a decentralized blockchain that is scalable and

secure. Protected against cyber threats, which they’ve been subject to

in the past, and are obviously continuously facing and tackling newer

security challenges. Additionally, the data is also backed up in Estonia’s

e-embassy in Luxembourg.

Practically, this allows someone to be verified during a KYC process

(Know Your Customer), login to private or public services, to encrypt

or decrypt files securely, and to legally digitally sign documents.

Note that e-signatures are allowed in the EU, through the eSignature

Directive, to replace handwritten ones.

Users of such system are thus in the center, practicing self-sovereign

identity (SSI), personal autonomy, in full control of who has access to

their data. The system allows for traceability and auditability. Citizens

can transparently see what data is collected about them, when, why,

who has accessed to them, revoke or keep this information, and more. That

is unless law enforcement requests access, but they’ll still be notified

once the investigation wraps up.

This can be abused but the country has shown a strong legal stance

whenever law enforcement or doctors took advantage of their

positions. The traceability of each access also makes it harder for

someone to touch the data without anyone else noticing — unlike

traditional physical cabinet storages. This enables more privacy and

empowerment that when a private company has control over personal data.

The advantages are obvious: designers of systems save time by relying

on the government infrastructure, and citizens too by carrying their

life activities online.

This includes banking, e-residency, accessing health records, medical

prescriptions, voting, paying taxes, and more. One thing they are

considering integrating is their own cryptocurrency.

Estonia also teaches cyber hygiene in elementary school. Education is

an important factor that we’ll dive into next.

The EU is considering implementing a similar system, but leaving each

national authority the choice. However, it is still being discussed and

argued if it should be mandated across all nations. They have agreed

on eSignature Directive, allowing electronic signatures to be the

equivalent of handwritten ones, and took a few steps with encouraging

national digital IDs in 2018 through the Electronic Identification And

Trust Services (eIDAS) regulation. The implementation of digital ID in

Europe would allow cross-border electronic transactions and electronic

signatures, but only 14 out of 27 member countries have introduced online

authentication systems, such as DigiD in the Netherlands, Belgium’s eID

card, and Spain’s DNIe.

Another large implementation of digital identity is India’s

Aadhaar. Technically, it is a non-compulsory 12-digit unique identifier,

termed Aadhaar, that also comes with a public-private key infrastructure

that stores biometric information.

Due to the non-mandatory nature, the government has to ensure that no

service can be denied if the person hasn’t signed up for Aadhaar. However,

in practice, many services are now using it for KYC as a replacement

for paper proof of identification.

Moreover, because it isn’t mandatory, Aadhaar isn’t a proof of

citizenship or residence: it doesn’t replace other IDs like passports

or driver’s licenses.

Aadhar practical form is as a biometric ID system, allowing citizens

to prove their identity by simply providing a fingerprint or iris scan

for example. There is also an ID card that can be issued.

On top of Aadhar, the government has rolled out a Unified Payment

Interface (UPI) allowing banks to interoperate with Aadhaar. UPI is

designed to make person-to-person (p2p) and e-commerce transactions swifter

and easier.

For India, this has been a game changer, enabling access to bank

accounts and services that most couldn’t access before, making them

more inclusive. Figures are not robust, but it can be assured that most

(4 out of 5) Indian citizens have the ID card.

This saves a lot of overhead, someone can transfer money simply by

showing their Aadhaar card, or paying with their fingerprint.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of criticism, calling it a

“tech-solutionism” and saying the roll-out has been discriminatory.

Besides, there have been emerging reports regarding the security concerns

of the personal data associated with Aadhaar ID being sold in alternate

markets.

These flaws in privacy and security need to be addressed with

accountability, traceability, and a strong legal framework, similar to

what Estonia is doing. So far, Aadhaar doesn’t yet seem to put the person

in control of their own information, self-sovereign identity. Plus, the

document could be upgraded to be considered a true proof of citizenship.

Additionally, only basic biometrics is not enough, but adding a smart

card with a pin to the mix was the way to go. It fulfills: something

you know, something you have, something you are.

The development possibilities are there and the outcomes would be

interesting.

China has slowly been pushing for its virtual/electronic ID card,

a digital ID. Practically, it is a valid national ID that contains

biometric information such as face and fingerprints.

The solution takes a mobile-first approach, as an app with QR codes,

and would integrate well with all services, both online and offline. It

is still in its pilot/trial phase, but would be a true replacement for

official ID cards and could be used within popular applications such

as WeChat and Alipay. For example, WeChat Payment is already extremely

popular for making digital payments.

China’s implementation would be directly inspired by Estonia’s one, very

similar. At China’s scale, like India, it would open a lot of future

possibilities as 67 percent of Chinese residents do not currently have

a credit record. The system would also be linked to a generic credit

score database.

China is also eyeing entering the digitalization of the supply

chain. Their Standardization Administration describes it neatly:

“First-class companies do standards. Second-tier companies do

technology. Third-tier companies do products.”

This means being able to associate identity and traceability of all

the supply chain and trade processes across multiple geographies and

organizations. A true verifiable life-cycle where you could identify

compliance and transparency.

For that, they’ve partnered with international standard organizations

such as ISO and ITU, and started designing and implementing the next

wave of standardization in cyber-physical trade with its ambitious

China 2035 Standards strategy. This initiative is also driven by other

organizations such as UN/CEFACT, the ICC, World Customs Organization,

the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), and International

Air Transport Association (IATA).

This type of digital meta-platform, this platform-of-plaforms, would

empower individual actors by giving them the power of traceability and

identity for supply chain & trade. This applies to both people within

it and outside it.

For the consumer, that would mean being able to reliably see the

origin of a product, including its materials, legal, geographical,

intellectual-property, its origins, and more. This is essential for many

of us, and would make it easy to see the quality of intangible goods.

Consumers, governments, and companies are demanding details about the

systems, enterprises, and sources that delivered and transformed the

goods along their value chain. They worry most about quality, safety,

ethics, and environmental impact, to name just a few.

This would ensure the transparency when buying products from big platforms

that contain sub-markets such as Alibaba, Amazon, and Wal-Mart. This

adds a lot of trust and transparency with consumers, they can verify the

digital twin of their physical good, along with its history.

Now, that is going digital!

A path towards societal digitalization through internet technologies.

Other countries such as Argentina, Afghanistan, Denmark, Pakistan,

Kazakhstan, and more have or are introducing national ID cards with

embedded chips used for services and are considering or in the progress

of integrating with biometrics, payment, and the online world just like

Estonia, India, and China are doing.

This seems like a global trend and is expected to increase with new

types of root of trust that can be shared over the wire such as IoT SAFE.

This concludes our review of how governments can bring back order, morals,

and ethics on the internet. In a first place, we’ve dabbled with how the

market isn’t enough and how there’s a need for laws that

would consider privacy as a human rights. Then we’ve seen the balance

between sociality and privacy, to whom we’d prefer giving it. Next we

went over three topics applied to legality: consent, accountability,

and transparency. After that we’ve looked at some examples, how the

world is moving in that direction. Finally, we’ve tackled identity and

social media as utilities and infrastructures, and what that would imply,

along with some of today’s examples.

Table Of Content

- Introduction

- Part 1: The Artifacts And Spaces

In this part we'll describe the important artifacts and places. Going

over these essential, but basic, pieces is mandatory to understand how

they come into play as tools.

- Part 2: The Actors and Incentives

In this part we'll go over how the previous elements are put into work

by the different actors, who these actors are, what are their incentives,

and the new dynamics.

- Part 3: Biases & Self

In this part we'll try to understand why we are prone to manipulation,

why they work so effectively or not on us, and who is subject to them.

- Part 4: The Big Picture

In this part we'll put forward the reasons why we should care about

what is happening in the online sphere. Why it's important to pay

attention to it and the effects it could have at the scale of societies,

and individuals. This part will attempt to give the bigger picture of

the situation.

- Part 5: Adapting

In this concluding part we'll go over the multiple solutions that have

been proposed or tried to counter the negative aspects of the internet.

- Conclusion & Bibliography

References

- Algorithms, bots, and political communication in the US 2016 election: The challenge of automated political communication for election law and administration

- The Tech Industry’s War on Kids

- STATE-SPONSORED TROLLING How Governments Are Deploying Disinformation as Part of Broader Digital Harassment Campaigns

- Platforms Must Pay for Their Role in the Insurrection

- Dark Pattern (Wikipedia)

- Just Don’t Call It Privacy

- ‘Weaponized Ad Technology’: Facebook’s Moneymaker Gets a Critical Eye

- New human rights to protect against ‘mind hacking’ and brain data theft proposed

- What’s Going on With France’s Online Hate Speech Law?

- Liberté de réception

- GDPR

- Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019

- Data Protection Act 2018

- Australia Passes Law Making Facebook, Google Pay for News

- Google says it’s confident about alternatives to browser cookies that track you for ads

- Lack of competition in ad tech affecting publishers, advertisers and consumers

- Percolation Theory

- On the Origins of Memes by Means of Fringe Web Communities

- Democracy of the Gullible 2020 DW Documentary

- What is Social Cooling?

- The world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data

- Social media as a utility

- Public Money, Public Code

- Towards a more sustainable single market for business and consumers

- Minister hints at UK departure from GDPR

- Facebook’s GDPR consent bypass via a “contractual advertisement duty” before Austrian Supreme Court, with high potential for a reference to the CJEU

- What’s Data Privacy Law In Your Country?

- Requests to delist content under European privacy law

- Find Out Where Apple, Facebook, Google, Twitter and Other Tech Giants Are Sending Your Data

- We can have democracy or we can have Facebook, but we can’t have both

- Who runs the world… Big Tech?

- Dark Patterns after the GDPR: Scraping Consent Pop-ups and Demonstrating their Influence

- How Neoliberal Policy Shaped the Internet—and What to Do About It Now

- Silicon Valley’s POWER GRAB - Can Big Tech Be Broken Up?

- Social media as a public utility

- U.S. Supreme Court rebuffs Facebook appeal in user tracking lawsuit

- No Gates, No Keepers — The technology industry is hurt at every level by toxic gatekeeping

- Gatekeeping in Online Communities

- You Can’t Censor Away Extremism (or Any Other Problem)

- Digital Identity in China: Today & Tomorrow

- Identity in a Multi-polar World and China’s 2035 Standards

- Is China The Roadmap — Or Red Flag — For Digital ID Verification?

- Nuances Of Aadhaar: India’s Digital Identity, Identification System And ID

- Inside Aadhaar, India’s massive digital identity program

- A Practical Guide to Data Privacy Laws by Country

- India’s billion digital identities

- Digital Identity: Towards Shared Principles for Public and Private Sector Cooperation

- Is India’s digital ID system, Aadhaar, a tech solution for a socio-economic problem?

- Privacy Act (Canada)

- What is China’s Social Credit System and What Does it Mean for Online Identity?

- Modernizing Canada’s Privacy Act

- HBR, 2010, The Transparent Supply Chain

- New China Data Privacy Standard Looks More Far-Reaching than GDPR

- Are We Automating Racism?

- HOW WILL WECHAT ELECTRONIC ID SYSTEM WORK?

- India’s new intermediary liability and digital media regulations will harm the open internet

- Racial Discrimination in Face Recognition Technology

- Online Privacy Law: France

- 533 million Facebook users’ phone numbers and personal data have been leaked online

- DigiD

- Identity management

- Self-sovereign identity

- Time to regulate AI that interprets human emotions

- Data Protection Commissioner (DPC)

- Digital Identity

- Electronic identification

- Honest Ads Act — USA

- How Estonia is Pioneering the Digital Identity Space

- GSMA Identity programme

- Google misled consumers about the collection and use of location data

- Estonian Electronic Identity Card and Its Security Challenges

- Booking.com fined €475,000 for reporting data breach too late

- What Estonia’s digital ID scheme can teach Europe

- GlobalPlatform Root of Trust

- Introduction to Secure Elements

- Hardware Security Module

- UICC

- SIM, eSIM and Secure Elements

- GSMA IoT SAFE

- New IP

- “Discussion Paper: An Analysis of the ‘New IP’ Proposal to the ITU-T.” Internet Society, 3 June 2020, https://www.internetsociety.org/resources/doc/2020/discussion-paper-an-analysis-of-the-new-ip-proposal-to-the-itu-t/.

Attributions: Michael Maier, Atalanta fugiens, Oppenheim, 1618

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

Utopia

Utopia

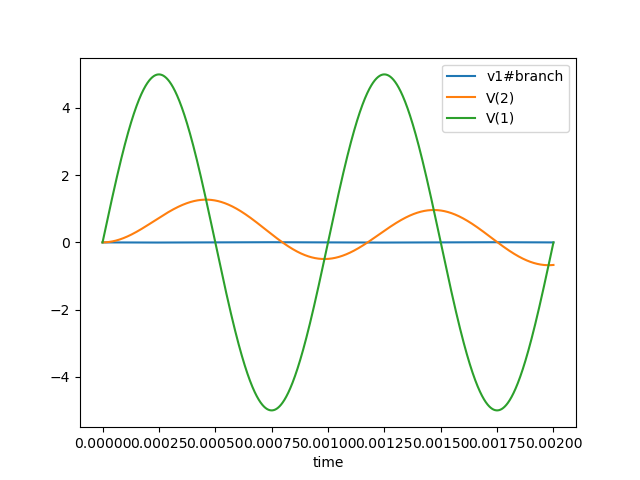

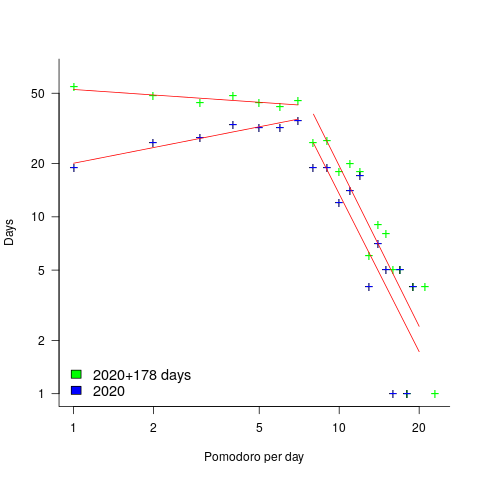

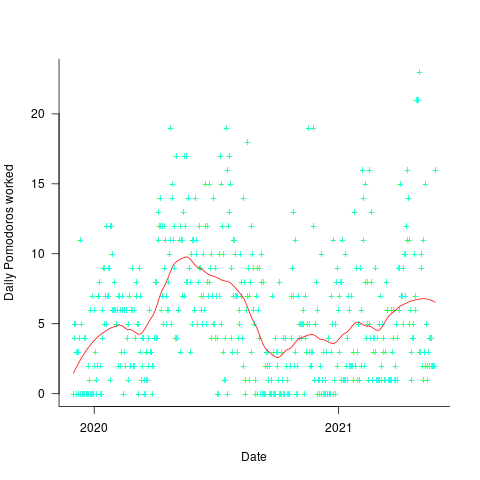

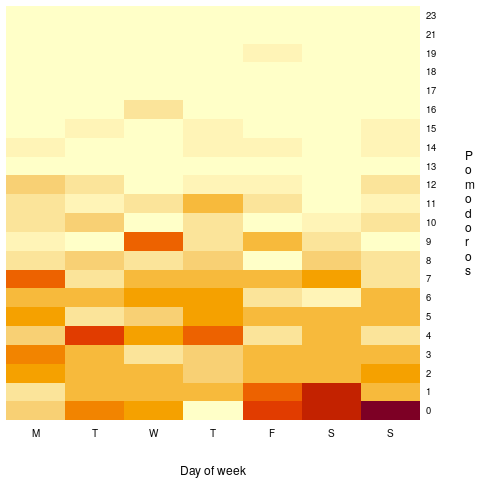

, where:

, where:  is the Pomodoros worked on day

is the Pomodoros worked on day  ,

,  Pomodoros worked on the previous day,

Pomodoros worked on the previous day,  is white noise (e.g., a Normal distribution) with a zero mean and a standard deviation of 4 (in this case) on day

is white noise (e.g., a Normal distribution) with a zero mean and a standard deviation of 4 (in this case) on day  the previous day’s noise (see

the previous day’s noise (see

Egy piros autó (a red car)

Egy piros autó (a red car) A view of Lake Balaton from Hegymagas, Hungary.

A view of Lake Balaton from Hegymagas, Hungary.

My first 7 day DuoLingo streak

My first 7 day DuoLingo streak

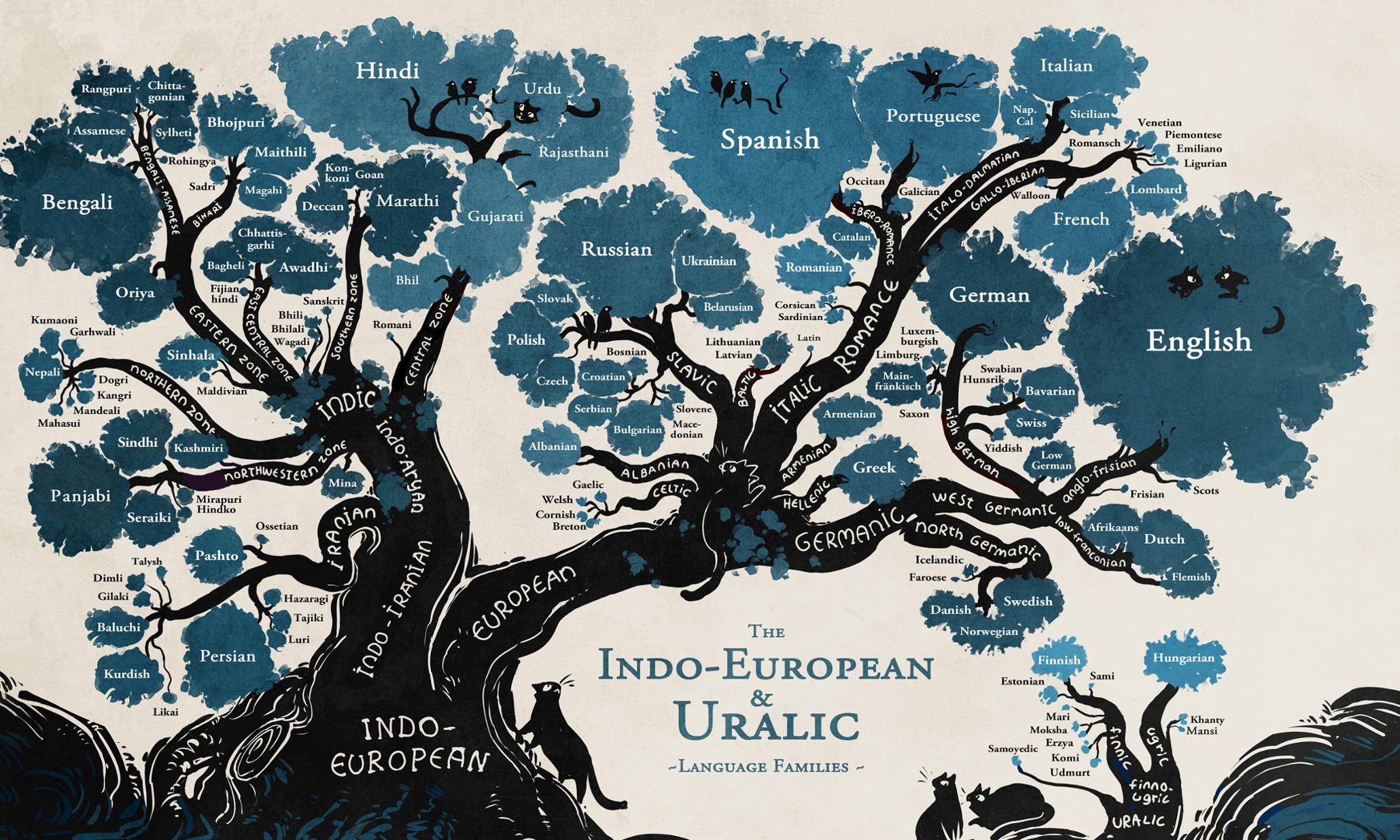

Hungarian and its closest relatives

Hungarian and its closest relatives

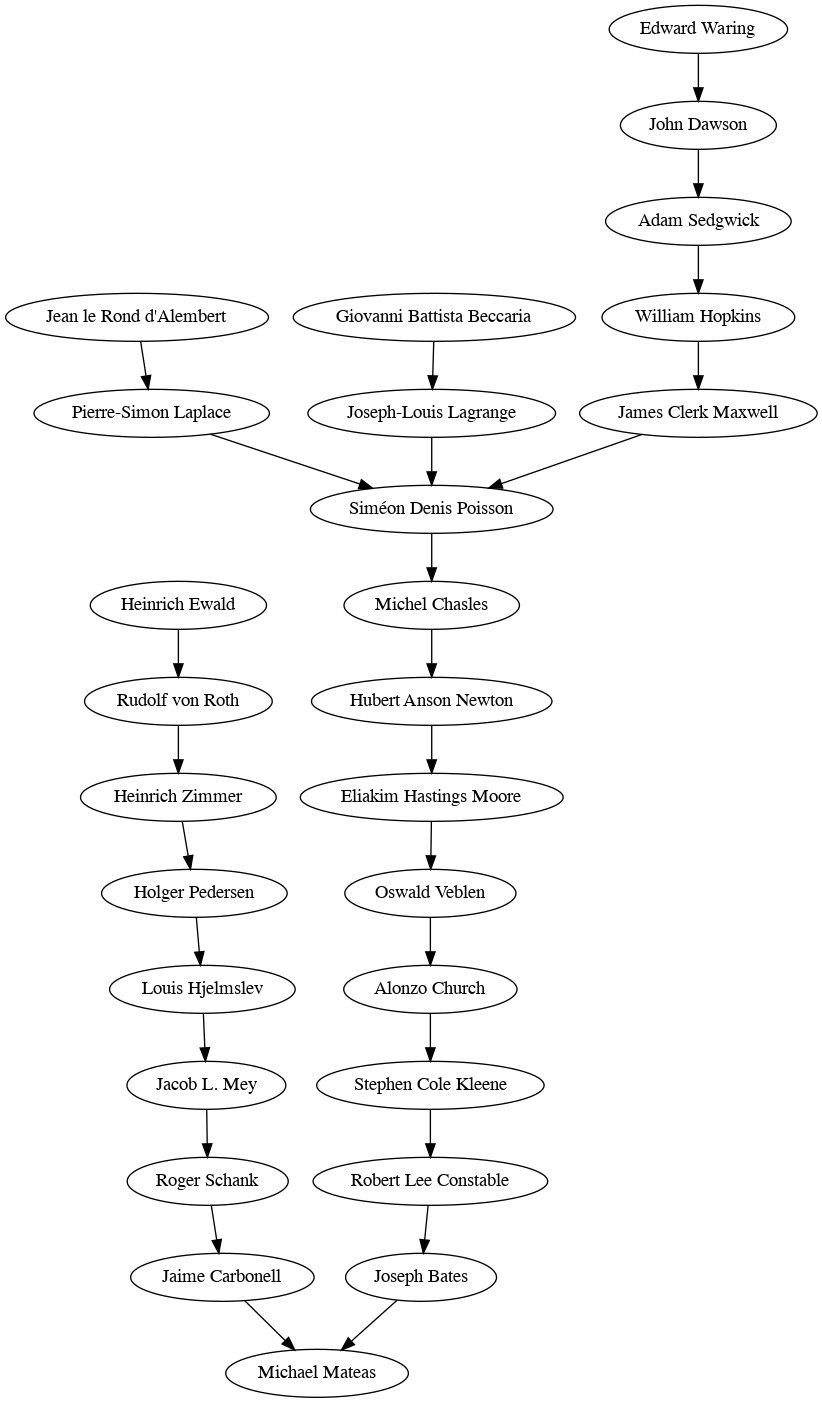

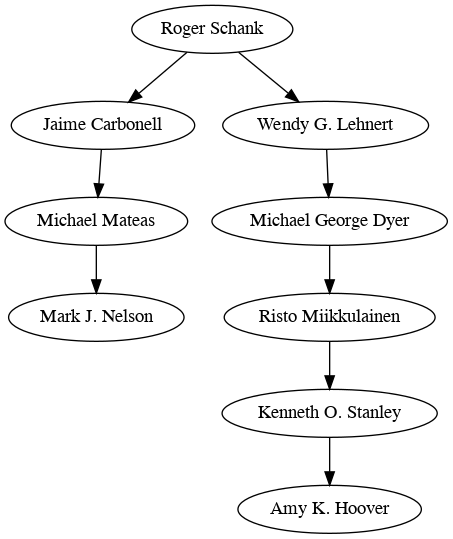

Family tree of the Old World languages, note how Hungarian and Finnish are so far removed from every other European language.

Family tree of the Old World languages, note how Hungarian and Finnish are so far removed from every other European language.

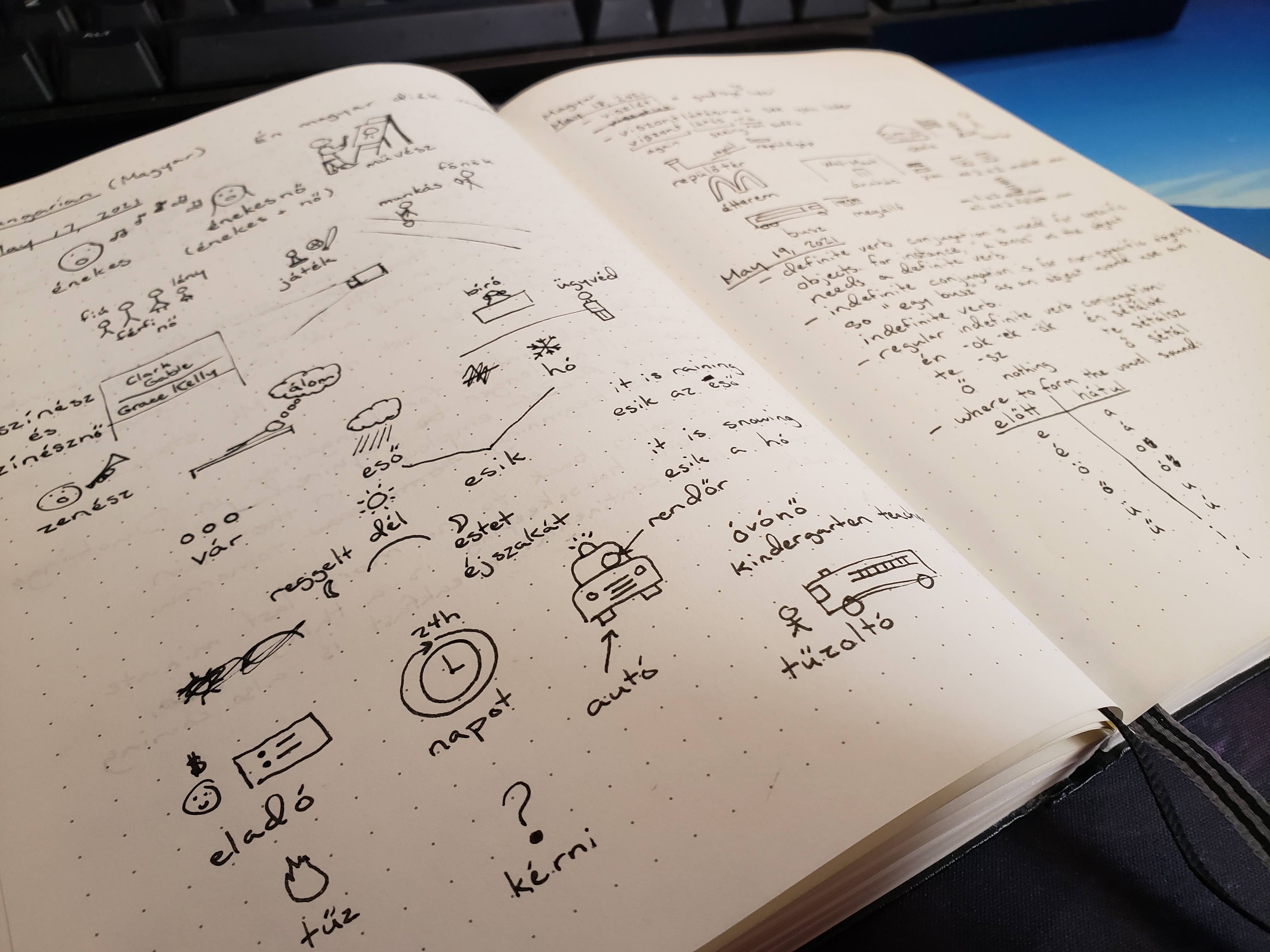

A couple pages of my Hungarian bullet journal.

A couple pages of my Hungarian bullet journal.

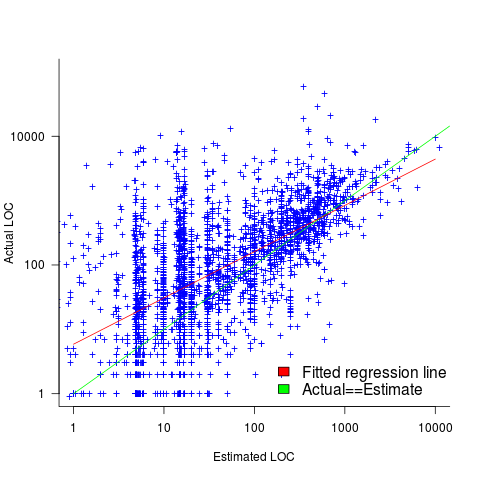

(the standard error on the exponent is

(the standard error on the exponent is  ), the green line shows

), the green line shows  (

(